Our paper “A Hyper-Catalan Series Solution to Polynomial Equations, and the Geode” is now available at Taylor and Francis Online. It will appear next month in print form in the American Mathematical Monthly. Here is the link to the paper:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00029890.2025.2460966

From the Abstract: The Catalan numbers 𝐶 𝑚 count the number of subdivisions of a polygon into m triangles, and it is well known that their generating series is a solution to a particular quadratic equation. Analogously, the hyper-Catalan numbers 𝐶

𝐦 count the number of subdivisions of a polygon into a given number of triangles, quadrilaterals, pentagons, etc. (its type 𝐦), and we show that their generating series solves a polynomial equation of a particular geometric form. This solution is straightforwardly extended to solve the general univariate polynomial equation. A layering of this series by numbers of faces yields a remarkable factorization that reveals the Geode, a mysterious array that appears to underlie Catalan numerics.

This paper is the outgrowth of a series of videos I made at my Wild Egg Maths YouTube channel starting in 2021. The basic idea had been mulling around in my mind for some decades, and every few years I would spend a week or two thinking about it some more. I just never liked that “solution by radicals” approach where even the cubic and quartic cases are so complicated that hardly anyone can remember them, and almost no-one ever uses them. Furthermore these “solutions” involved “cube roots” as well as “square roots”, invoking irrationalities that I just no longer believe in. There had to be a better way!

Happily Dean volunteered to help me put together a paper on this topic. His input has been invaluable, and the paper is a reflection of his commitment and hard work.

It turns out that the better way to solve general polynomial equations already has its seeds in the quadratic case. There the usual quadratic formula involving a square root of the discriminant b^2-4ac can be expanded by using Newton’s power series extension of the binomial theorem, yielding a series solution involving the Catalan numbers C_n, that famous sequence 1,1,2,5,14,42,132,429,1430,4862,16796, … (A000108 in the Online Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences (OEIS)).

But why should these numbers, originating in Euler’s counting of the number ways of triangulating a fixed convex polygon in the plane by non-intersecting diagonals, and now connected with literally dozens (actually probably hundreds) of other counting problems in mathematics, have anything intrinsically to do with quadratic equations?

An intriguing answer is given in Exercise 7.22 of the classic text Concrete Mathematics by Ronald Graham, Donald Knuth, and Oren Patashnik — and which they further attribute to George Pólya’s On Picture Writing. The idea is to generate an algebra of triangular subdivisions of convex planar polygons and consider an associated polyseries (formal power series) that keeps track of how many triangles are involved at each step.

So the short story is that we use that idea and extend it to the more general situation where a planar convex polygon is divided, by non-intersecting diagonals, into a certain number of triangles, quadrilaterals, pentagons etc. We keep track of how many of each by a vector, or list m=[m_2,m_3,m_4,…], where m_2 counts the number of triangles, m_3 counts the number of quadrilaterals, and so on. Then we introduce the hyper-Catalan number C_m to be the number of subdivided roofed polygons that have exactly that many of each in the subdivision. Here “roofed” means that there is a distinguished side of the convex polygon, that we declare to be the top. This gives a new array of numbers depending not just on a single subscript, but potentially on a finite number of an ongoing list of possible subscripts 2,3,4,…. These we call the hyper-Catalan numbers.

Then we construct an algebra from a sequence of panelling operators, generalizing the one of Graham, Knuth and Patashnik on a multiset of subdigons, which is what we call our arbitrarily subdivided planar roofed polygons. Ultimately we use the simple fact that an arbitrary subdigon is characterized by the subpolygon directly under its roof, in addition to all of its directly adjacent polygons, which are themselves subdigons.

By analysing this geometric relationship, we get an algebraic equation satisfied by the big multiset of subdigons, and then the associated polyseries which is a polynomial in variables t_2,t_3,t_4,… turns out to solve a general polynomial in alpha whose coefficients are 1,-1 for the 0-th and 1-st degree terms in alpha, and whose subsequent coefficients are t_2,t_3,t_4,….

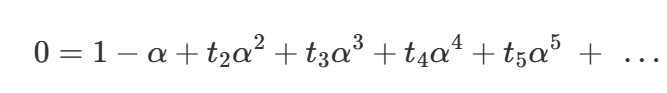

Here is one statement of the essential formula that results: The polynomial equation

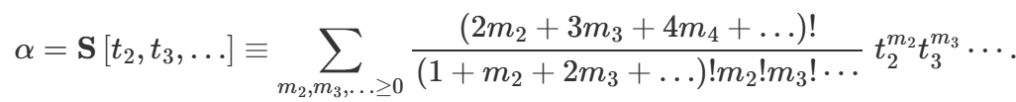

has a solution

where the coefficient with the factorials is an explicit expression for a hyper-Catalan number, obtained over many decades, going back to work of Erdelyi and Etherington in the 1940’s, by several combinatorialists.

We show that it’s not too hard to go from this formula to the solution of the general equation by a simple change of variable, and then apply this to Wallis’ famous cubic equation x^3-2x-5=0. Our solution uses just one simple truncated line of the general series, namely

Using this we can, by starting with the guess x=2, generate with two passes (we employ a kind of boot strapping) the approximate solution x=2.0945514815423265098 which agrees with our computer to 16 decimal places.

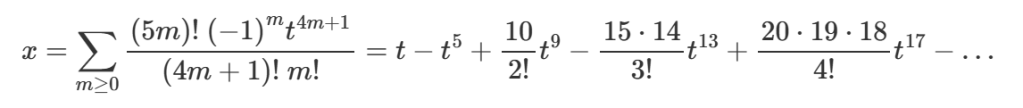

We also show how to now solve a quintic (degree 5) equation, which is deemed impossible by the “solution by radicals” approach (the famous result of Abel, Ruffini and also Galois), and illustrate the idea on a special case recovering a series solution of Eisenstein for the (Brings radical) equation -t+x+x^5=0, namely we obtain

It turns out that our solution has an intimate relation to Lagrange’ reversion of series formula. Lagrange was one of the giant pioneers in the classical search for solutions of polynomial equations, and it is ironic that work that he did in the analytic direction ends up providing a beautiful channel towards the series solution that we have found. In fact this series solution was also obtained by by Joseph B. Mott in remarkable self-published work of 1855. This seems to have been completely forgotten about until now. I think we need to learn more about Mott and his story.

One of the further quite lovely consequences of our solution appears when we analyse the multidimensional array S[t_2,t_3,t_4,…] and its connection with Euler’s polytope formula V-E+F=1 for a subdivided polygon into V vertices, E edges and F faces. We end up getting a factorization when we organize the series S by the number of faces F=m_2+m_3+m_4+….

By introducing the polyseries S_1=t_2+t_3+t_4+… we prove in Theorem 12 (The Subdigon Factorization Theorem) that there is a unique polyseries G for which S-1=S_1 G. We call this G the Geode series. In some crucial way, the Theorem is asserting that this quite mysterious array is underlying hyper-Catalan number numerics.

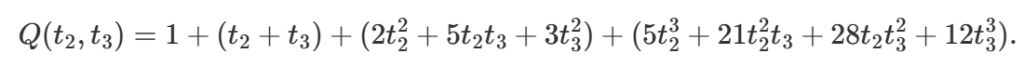

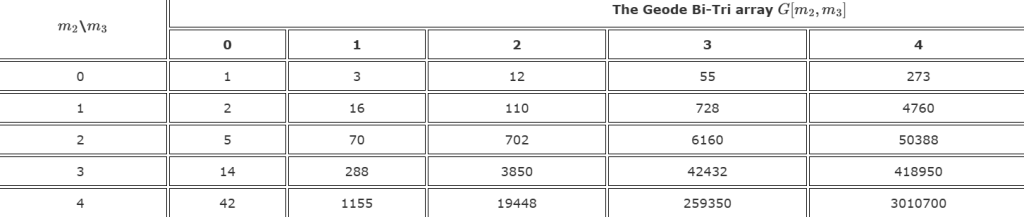

Here is a slice just involving t_2 and t_3 of this multidimensional Geode array:

Catalan and Fuss numbers appear down the first column and row, but the rest is an enigma — we can’t find any further connections with the OEIS. Nevertheless, we offer up some intriguing conjectures on the Geode array that might help with further investigations. But it is clear that there is a lot more to study.

At least now undergraduates have a clear cut alternative to the usual Galois theory courses that treat this classic problem in algebra. Both Euler and Lagrange would, we hope, be approving.